Family safety depends upon the ability to know what others see when they gaze upon your group.

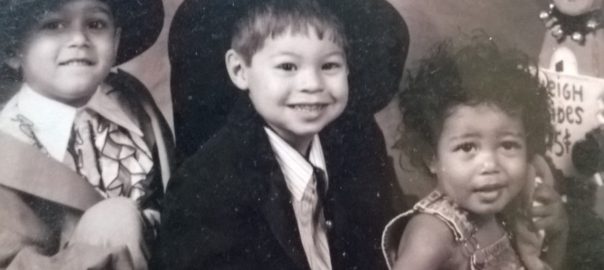

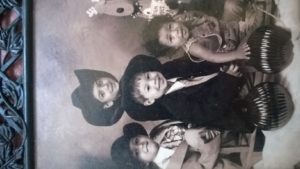

My daughter took her four young children to the photographer. She wanted a professionally crafted picture of her boys. It was an excessive expenditure meant to cement them as “Four Brothers, One World!” In fact, eventually, years later, she would make them a website bearing this motto meant to promote diversity as well as solidify her wishes. But that is closer to now and this story was then. .

My daughter’s sons were a bit of a rainbow collection. She had mixed her very white genetics into two Arabs, an Italian, and an African American. She was happily married to the father of her youngest son. Their family was very diverse. Hubby came with his own bag of mixed children and grandchildren and together they could fill a room with a variety indicative of differing ages, races, sexes, and gender identifications. Though she embraced them all she also wanted to engender a tight connection between her own biological four. She wanted for her sons what she had gained for herself. She affectionately recalled the many years of absolute commitment to and from her own biological sister. She even recalled the moments when she chose to cultivate that closeness. She hoped they might evolve into relationships that were similarly purposeful.

So she took them to the photographer. To create a memory. To begin a process.

It was common in those days to offer affordable family pictures that included costuming, which this one did.

A few weeks later she resisted the sales pitch and multiple single shots, picked up the eight by ten version of the one and only group picture she could afford and brought it home for all to see. It was all caps ADORABLE! Totally the cutest picture I had ever seen. Delighted she showed it to her sister, who laughed, “Oh My God! Declyn is dressed like a slave.”

OOPS!

We all looked again. She was right. His brothers looked like the wealthy slave owners while he looked like the happy little whipping boy to be.

Thus it was that those of us who hadn’t seen the symbolism before my younger daughter pointed it out saw it now; kind of, but not really. Declyn in his curly haired, shirtless overalls and one cheek dimple just looked too cute to us. We understood what she was saying but it didn’t seem important so we saw it but we also didn’t. In our white-skinned defense to us, slavery wasn’t really a thing. We are originally from Canada so slavery wasn’t in our history books and we didn’t know anyone with memories on the subject. For us slavery was more relatable as a game of role-play, like actors in a movie. Or, in this case, child actors playing dress up for the camera. We were more than color blind; we were assumption blind. “How could anyone see it as anything but a cute little slave and his white owners?” And still we didn’t hear the insult. It was picture perfect.

To us.

Who were not black.

And did not grow up with this photo proudly displayed on the figurative mantle.

The photo wherein three looked like masters and only one like a slave.

Childhood reflections are visual, memories are written by any story the mind sees.

My grandson was about five and laying on the floor of the back seat of my car. He was a creative introverted boy. Whenever he chatted from some hidden location the freedom of not being able to see the person he was talking to react let his mind wander. His stories swirled in the chasm between experience and imagination. He was jabbering on and on about this new town we had moved to and how Santa Clause created the world. He insisted that the lights glittering from the houses proved his point. It was Christmas and all the colored elves had finished making the toys. Santa Clause was Jesus and Jesus was coming. “What are the colored elves doing?” I asked. “Sleeping on the couch. That was a lot of toys.” How cute it all seemed. He was mixing it all together, adding the influence of his hardworking dad, trying to make sense of the stories in his head.

My grandson was about seven. He was doing well in his new school. He is super smart and excels at everything, and I mean everything. He came home one afternoon and said, “I know what they call the school White Oak.” “Why?” his mother asked. “Cause they filled it up with white kids.” We hadn’t noticed before but he was right. Declyn was the token black boy. And now that we saw it we couldn’t unsee it. But it didn’t seem bad, just like a coincidence of no concern. He was so cute and smart. Even if there was racism it couldn’t possibly be aimed at him, we assumed.

My grandson was about twelve. He got up and turned off the T.V. before the movie ended. “Why are the bad guys and expendable characters always black?” I had no answer. I had never noticed that. But once he said it I noticed it too.

He wanted black movie heroes, video game characters, and army dolls. These things happened, unfolded over time, we even had a black president for a while. Progress, right? Except for the photo so proudly displayed on my dresser, I might be able to agree.

My grandson was a teenager in a small town near Dallas. He dealt with a lot of deflected anger during the Obama years. I started to see color more clearly: mostly the color white.

Over the years, each time he shared, we found his observations of racial difference cute. And then learned a little something. Each time he shared we saw the wallpaper that black people live with a little more clearly. During this unfolding, my own skin often embarrassed me.

But when the Black Lives Matter movement first began I still found myself softly insulted. I wanted all lives to matter.

Because all lives do matter. In my race for equality, I wanted to skip the step of atonement.

And then a few years later George Floyde was murdered on camera and I was quarantined long enough to watch his life ebb away, missing breath by missing breath. I felt heavy with pain. And knew there was only one way out.

That is when I realized, atonement is good for the soul, even the collective one.

Progress depends upon a society’s ability to see difference, with open arms and a discerning eye.

Personal development depends on it even more.

I was cleaning out my closets when my eyes lifted to the photo of my grandson as a slave.

It was no longer cute, though he will always be.

I didn’t want him to live with this wallpaper anymore than the protesters want their society of colored friends to live with the statues of idolized slave owners and torturers.

Sometimes you just have to pull it down.

I want my grandson to move forward into his future without being told that his father was probably happy while he picked cotton and watched friends hang from trees. I am sure his father was happy at times but the low-grade fear and anxiety shaped him, turned him into someone that keeps his head down while working hard and avoiding eye contact with white people.

I want my grandson to stand on equal footing with everyone, to look into anyone’s eyes without a second thought, to unhesitatingly speak his mind and to feel liked by those who care to see, I cannot make him be those things. But I can do my part to stop preventing the possibility.

So I took the picture down from my shelf and shared it with you.

I shared these bits of his life, these bits that were shaped by my colorblind eyes, in case it helps you see, without the wallpaper.

Learning is a selfish act until it is shared with another.